Last week, on Oct 14th, I presented the findings of our Pesticides in Paradise report on the island of Moloka‘i, Hawaii. At around 5:45 PM, about 15 minutes before the presentation was going to start, 100+ Monsanto employees, all dressed in neon yellow shirts, arrived.

As I stared at the long line of workers, men and women of all colors and ages and sizes, entering the building, there was a moment when I wanted to walk away. I walked to the bathroom and sat with my face in my hands. I am not brave enough for this confrontation. I am not the right person to deliver this message. I am not strong enough for the yelling and fighting that will likely ensue. Deep breaths. Air punches.

I re-entered the main hall, now crowded with community members, workers. The island is so small that I already recognized faces from the four days I had spent here. My team gave me half horrified; half encouraging looks as I paced the front of the hall. With a few deep breaths and a nod from the few friends we had in the audience, I began.

You can watch the full video un-edited here:

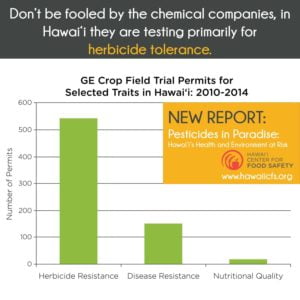

The presentation walks the audience through data on pesticides and genetically engineered crops in Hawai‘i and the medical literature that examines the human health and environmental impacts of pesticide exposure, on pregnant women, children, and farm workers, who are particularly vulnerable to adverse health effects.

And here in lies the greatest challenge of that night and the greatest opportunity. Although seemingly there to intimidate me and oppose our message, these 100+ people are the most at risk from the growing GE Seed industry in our state.

Workers exposed to restricted use pesticides have higher rates of chronic diseases such as bladder and colon cancer, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Parkinson’s disease, and depression. Children who live in and around agricultural operations like those owned by Monsanto and Dow are vulnerable to chronic, low-level exposure to restricted used pesticides that drift from GE test fields on a weekly basis. In utero and early life, children are at a risk of neuro-developmental disabilities like autism and ADHD, leukemia, and asthma.

Communicating the very real risks posed by this industry to the workers and their families, implicating their employers in these dangerous practices, is difficult… but necessary. As I walked through the information, some in the audience shook their heads. Some looked confused. Others seemed as though they were prepping for battle, taking notes and referencing a packet I would come to learn was a briefing paper provided by Monsanto.

But, there were 20 or so audience members, in their bright yellow Monsanto shirts, who leaned in. Eyes wide, chin on hands. Listening. Absorbing. Many were elders who have seen what large agricultural companies can do to communities. Others were women concerned about their children and their husbands.

By the time I had wrapped the presentation, the agitation in the room was palpable. The company spokespeople had their time on stage, rallying the crowd to cheers of opposition, repeatedly asserting that the information we were sharing was false…. “These are the real experts on pesticides,” said Ray Stevenson, president of the Molokai Chamber of Commerce gesturing to the Monsanto workers. “No one knows agriculture and pesticides more than the people of Moloka‘i.”

I couldn’t stop thinking about those 20 or so workers who leaned in. Those eyes that widened as we talked about developmental delays in children, and higher cancer rates in agricultural workers. I wondered, as I saw the executives shift uncomfortably in their seats, if they regretted inviting their workers. Did they realize that seeds were planted? That we will continue to water these seeds and that this is how transformation grows?

As we cleaned up the hall, Robert Stevenson approached me. He thanked me for coming over and offered a word of warning. “I hope you remember, next time you come to Moloka‘i, that this is what our community thinks about your work and this is where we stand.”

I responded, “I understand, Ray, that what we’re sharing is not popular and that conversations like these are hard. But I’m not here because I think what I’m doing is popular. I’m here because I think what we are fighting for is right. Whether you like it or not, the demand for greater pesticide regulations, for disclosure and buffer zones, for the protection of families and workers, it not going anywhere… What we are asking for is absolutely reasonable. I’m here to have hard conversations like this until the protections for workers and families are not a debate – but a hard-won reality.”

Nights like this are the real decision-making moments when you are engaged in their hard work of advocacy and community organizing: when you stare Goliath in the face, in all his shifting forms, and you connect to the deepest reservoirs of passion, commitment and courage that exist within you to stand up and speak hard truths. I’m certainly not the first person in our community to stand up in the face of over-whelming opposition. In fact, I take inspiration from all the people I work with who channel this courage in their families, among friends and co-workers, everyday. But standing up and speaking out is important. It’s what is going to ensure the health and safety of our communities for generations to come.

Ashley Lukens is the Program Director for the Hawaii Center for Food Safety. Her work focuses on issues of human and environmental health as they relate to the food system. She has her PhD in Political Science from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, where her research examined community-led efforts to develop culturally appropriate strategies for food system transformation.

Ashley Lukens is the Program Director for the Hawaii Center for Food Safety. Her work focuses on issues of human and environmental health as they relate to the food system. She has her PhD in Political Science from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, where her research examined community-led efforts to develop culturally appropriate strategies for food system transformation.

Submit your story or essay to Buzzworthy Blogs.